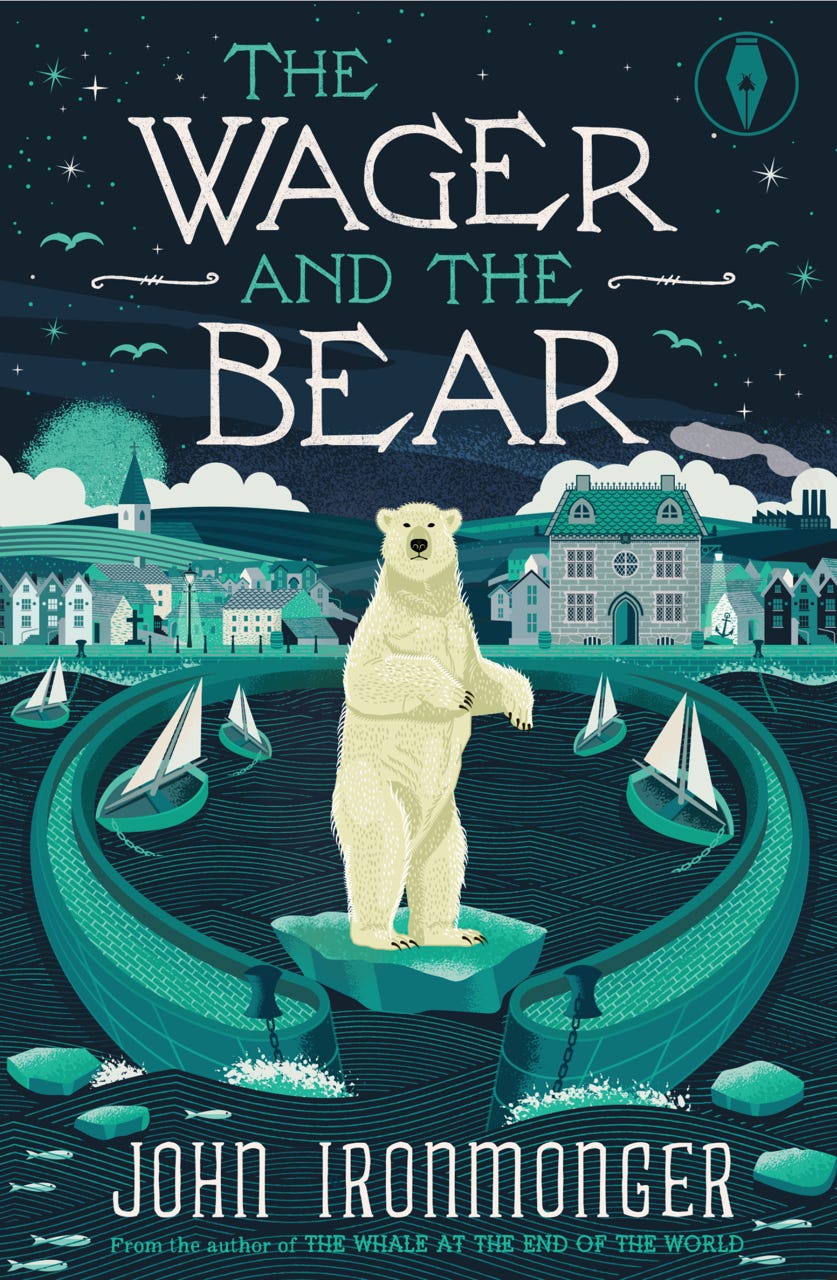

The author of The Wager and the Bear, in which two feuding friends end up trapped on an iceberg together, discusses writing and Bowie.

David Bowie had a remarkable talent for writing songs that could conjure up a story. It is impossible to listen to ‘Space Oddity’ without imagining Major Tom, sitting in a tin-can, drifting forever into space. But the Bowie song that stays with me most is ‘Five Years’. It tells a very simple story. News has reached us that the earth has only five years left. The planet is dying. In the song, the newsreader weeps. All around the market square people lose their minds.

What would it be like, I have often wondered, if we really were told this news? If a solemn news report, backed by all the world’s serious scientists, was to tell us we were running out of time? How would we react?

Well it just so happens that we know the answer to this question. Newsreaders wouldn’t weep. No one would go crazy. We would ignore the danger and carry on with our lives as if nothing had changed. We know this because this is what we do. Every few months the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produces a new report telling us the planet is running out of time. Every year the COP climate change conference makes dire predictions. Every year we learn that the previous year was the hottest on record. We watch forest fires in places like Canada and Brazil. We see dramatic floods, powerful storms, devastating droughts. We witness the collapse of animal populations. World leaders fly in and out of conferences. They make vague promises. But very little changes. And the world continues to die.

The challenge seems to be a failure of human imagination. Perhaps it is the timescale. If the axe was destined to fall in just five years, we might be more alarmed. If it was an asteroid hurtling towards us, we might make a real global effort to find a solution. But climate change seems to be a long unfolding tragedy. We are like passengers in a slow-motion train crash. The train is heading for a precipice, and all the pieces are in place for a terrible disaster, but everything is moving so slowly we stop worrying.

All this presents a particular problem for story tellers. Climate change is the biggest story of our time, yet very few novelists are ready to grapple with this. Ten centuries from now, if humanity is still around, I suspect historians will only be interested in one story from our generation - how we responded (or failed to respond) to this existential threat to the planet. Science fiction, in general, has done us rather a disservice here. Writers have sold us either Mad Max-style desert dystopias, or impossible tales of starships taking survivors to new green planets. What we don’t have enough, are real world stories that could help us to imagine the kind of earth we are creating. And that is a shame, because imagination is what we need, now more than ever.

Once again, timescales seem to be the challenge. Novelists need a central protagonist with whom readers can identify. This character needs to have a story arc, and human dramas are typically too short for climate change to feature very much. There is a second problem too. It is hard to imagine any character playing anything but a very minor role in what is a huge global drama. No one is going to step forward like Bruce Willis and save the world. For a writer, that is an unhelpful backdrop. We do not like to set up a jeopardy for our characters, without giving them some way to fight back. But how do you fight back against a warming planet?

In my novel, The Wager and the Bear, I hope I may have found a way to navigate a little around these two problems. The narrative unfolds over a whole human lifetime, and the central characters are front-seat observers of the climate disaster. The story involves two young men. One, Monty, is a politician. He is a climate change-denier. He lives in a grand house on the beach in Cornwall. He has a splendid lifestyle, and like so many of us in the slow-motion train crash, he doesn’t see the precipice approaching. The second man, Tom, is a climate scientist and campaigner. One drunken night, over too many glasses of cider in the local inn, the two men get into a quarrel. It ends with a deadly wager. In fifty years, either the sea will rise enough to drown Monty in his beach-front home, or Tom will accept the jeopardy himself, and will walk into the sea and drown. A video of the wager, posted online, goes viral. How will it all work out?

Well we have fifty years for the story to unfold. The lives of the two men cross several times, leading them both onto a melting glacier, and ultimately onto an iceberg floating down the coast of Greenland where their only companion is a hungry bear.

The story is not entirely without hope. It is set against the backdrop of a campaign to restore some of what the world has lost. Neither Monty nor Tom can save the world. But there is at least hope, as well as despair.

Climate change doesn’t have to be front and centre in contemporary fiction. But we shouldn’t be ignoring it either. As writers we have a responsibility, sometimes, to make the future seem real. We are hurtling towards a world of human-made disasters, of dying oceans, of rising seas, of failing harvests, of droughts, of economic collapse, and of climate-driven conflicts. We cannot ignore these things. If these aren’t part of our fictional landscape now, then they need to be. Otherwise one day we may find we have just five years left. And it won’t just be the news readers weeping.

A version of this article was published (in Italian) in the newspaper Repubblica in November 2023

Find out more about The Wager and the Bear.

John Ironmonger was born and grew up in East Africa and is now based in Cheshire. He has a doctorate in zoology, and was once an expert on freshwater leeches. He is the author of The Good Zoo Guide and the novels The Notable Brain of Maximilian Ponder (shortlisted for the 2012 Costa First Novel Prize and the Guardian‘s Not the Booker Prize), The Coincidence Authority and The Whale at the End of the World (an international bestseller). He has also been part of a world record team for speed reading Shakespeare, has driven across the Sahara in a £100 banger, and once met Jared Diamond in a forest in the middle of Sumatra.

Read Climate Fiction that Inspires Possibility

Imagine 2200 by Grist Magazine showcases visionary stories of climate resilience and community-centered solutions from writers across the globe. Inspired by Afro- and other futurisms, and solarpunk, these stories challenge us to remember: At the heart of climate solutions is human promise, ingenuity, and hope.

Be the first to know when our new stories are published! Sign up today to get brand-new climate fiction in your inbox.

Sign up here: https://go.grist.org/signup/imagine-email

It is pretty easy to write climate fiction set in the present. It is pretty impossible to get it published because everyone seems to believe it has to be set in the future when all has failed. I have a climate fiction mystery, The Earthstar Solution, set in today time, that I couldn’t even get listed here in Climate Fiction Writers League. We are not going to get more present day cli-fi that inspires people to take action now without support for those stories. If I can do it, others can write them too, but the support has to be there. I always say… if we want things to change, we have to imagine it. Write about the change we need now. And then help by spreading the word about those type of books.

Recently a friend said dystopia has been normalized, and I have to agree. Rather than indulge in speculative variations on the theme of doom and gloom, she wished for a Time Machine to go 50 years into the future to see how things actually turn out, since if there is one thing humans are good at it is muddling through impossible situations.

But do we really need more cli-fi? Sci-fi back in the day often assumed a post-apocalyptic world— usually nuclear war (still a distinct possibility!). Now the cli-fi sub genre has decided anthropogenic warming of the planet will be our Armageddon. Other variations on the end—of-the-world as we know it theme have robot overlords or zombie virus running amuck. William Gibson describes the “jackpot” scenario where all sorts of horrible possible outcomes converge.

Are there any possible visions of the future that are not dystopian, not utopian (which everyone agrees are no-where/impossible), but are feasible and practical? Perhaps a “eautopia” where we recognize our common denominator— water, which makes up most of our bodies and is essential to life as we know it. Anyone remember “Stranger in a Strange Land?” Maybe a modern day version with a happier ending. ,