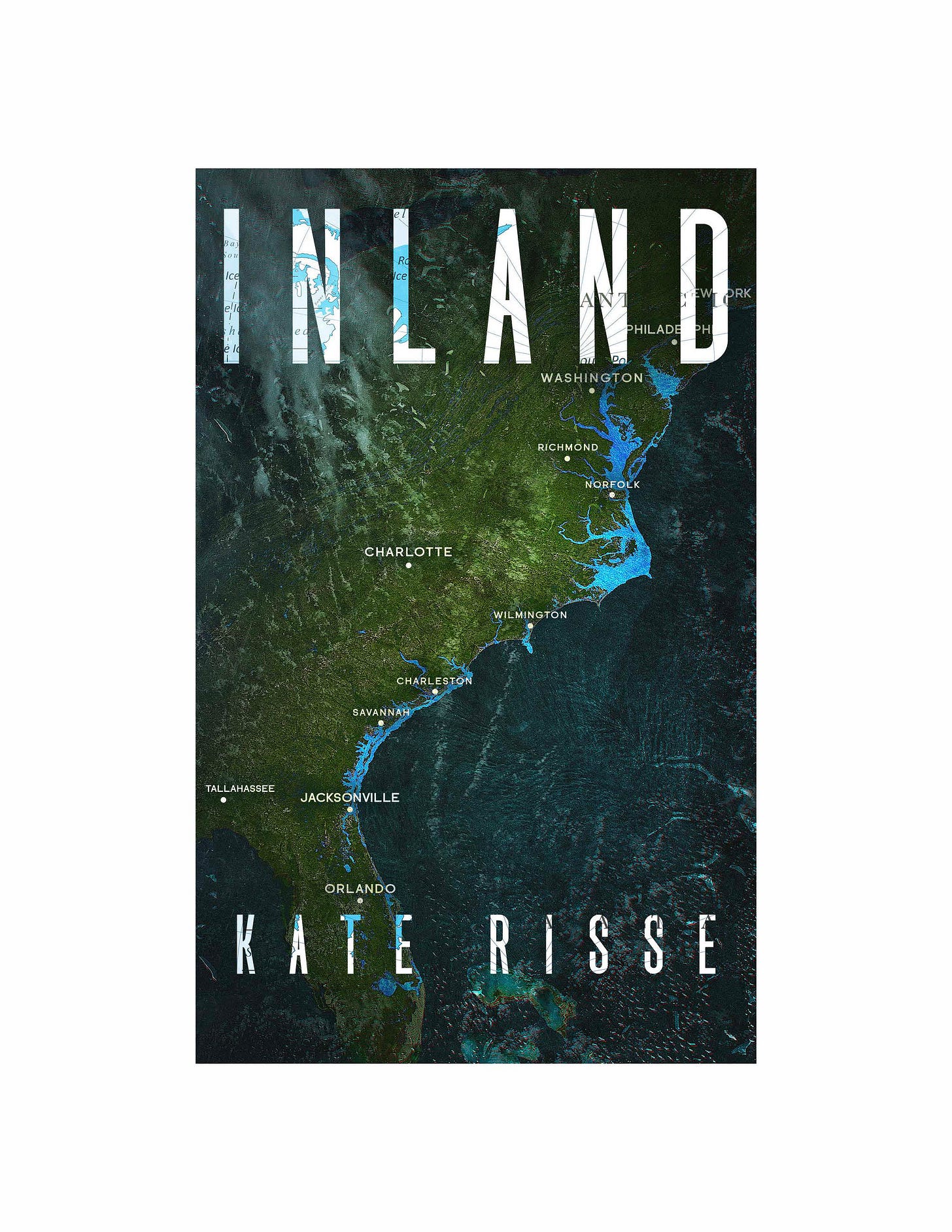

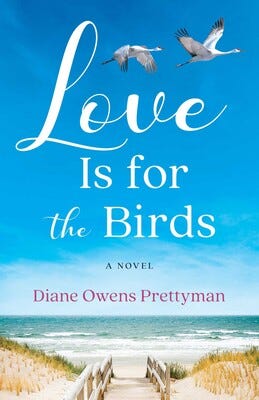

Kate Risse, author of adult dystopia novel Inland about a flood on the East coast of America, talks to Diane Owens Prettyman, author of women’s fiction novel Love is For the Birds, about a whooping crane refuge in the wake of a hurricane.

Diane Owens Prettyman: Kate your novel, Inland, jettisoned me to a different place. I normally don’t like dystopian themes. In your book, the characters and circumstances don’t seem to exist in some place far into the future. Your writing made this flooding event very real and in the realm of possibility. I think of the horrific flooding in North Carolina, for example. Why did you write this book and what do you hope readers will take away from reading the novel?

Kate Risse: I consciously placed my characters in the mid-2020’s to emphasize that these changes to the climate are happening now. I consider my novel a work of climate fiction. There is a movement within this genre to create worlds that resemble our own. Writers from Kim Stanley Robinson to Lily Brooks-Dalton have chosen the mid to late 2020’s to emphasize that we have arrived at a dangerous point, surpassing the 1.5 degrees Celsius that scientists have warned us about. The plot of my novel was shaped directly from concerns I had about raising children in a warming world. I hoped my book might contribute to the growing genre of cli-fi and general cultural discussion about the changes we see around us and how we are going to adapt. Fiction, however, is not science but I do think it can work with real-life scenarios to help us envision where we’ve been, where we are, and where we might be going.

Diane, in your novel Love is for the Birds you describe the hurricane’s destruction of the island: from animal habitats to the protagonist, Teddy’s, Candy store. You do not directly point your finger at the science of increased hurricane activity, but there is a sense that the weather event you describe is not normal and has devastated this tight island community: the people, the animals, and the environment that sustains them. You say that the aftermath of the storm “looked like hell, with everyone out to lunch.” And that some called it “The storm of the century.” Did you consider the role of climate change in those descriptions?

Diane: In writing this book, I didn’t deliberately intend to send a message regarding climate change. I wanted to share a story that would reach the hundreds of thousands of people who travel to the Texas Gulf each year. In Texas, many people are resistant to the term ‘climate change’.

I hoped that by telling a story about the devastation of the hurricane and the threat to the endangered Whooping Cranes, readers might recognize the importance of climate and care of the earth without blatantly preaching about it. The Whooping Crane story heralds the benefits of conservation. Once on the brink of extinction due to habitat loss and hunting pressures, concerted conservation efforts have saved this last wild flock from extinction. The population has grown from a low of 21–22 individuals in 1941 to 802 captive and wild individuals in 2021. Today, the Whooping Crane serves as a symbol of hope, highlighting the importance of habitat preservation, species recovery programs, and international cooperation in safeguarding endangered species.

Kate, the East Coast terrain is described vividly in Inland. Tell us about your experience living there and why you set your novel there? Do you have personal experience of climate change and loss of beach front?

Kate: I spend time on a Florida Gulf Coast barrier island south of Tallahassee. I’ve seen close-up the effects of the destruction of super charged water events: Hurricane Michael did a lot of damage to the Island where we spend time. Houses were swept away leaving nothing but a few chunks of concrete and a vast expanse of dunes. Friends and family visiting the island used to stay in a beautiful old, large, partially abandoned inn on the island. It got obliterated in the storm. Nothing left.

I’ve driven back and forth to the island: Boston to Florida and the reverse. I’ve seen some extreme weather and its aftermath along the Eastern Seaboard, including encroaching Atlantic waters in New England and big, destructive inland floods.

Both of us have written about islands: insular, tight communities, where cooperation and camaraderie are essential, the unique terrain and wildlife. Island represent both sanctuary and isolation. Talk about why you chose an island. Do you have a particular connection to an island and if so, how did that connection help sculp the plot line and the characters who are very much invested in its wellbeing?

Diane: Port Aransas is a barrier island off the Texas Gulf. As an avid boogie boarder, I have travelled there every year for at least thirty years. When the hurricane hit Port Aransas in 2017, I was devastated. My favorite condo complex was destroyed. After five years, it finally reopened. Other businesses returned surprisingly fast. The story of the town’s remarkable recovery and the threat to the Whooping Cranes habitat inspired me to write this novel.

I enjoyed every character in Inland. As a writer, what tools did you use to tap into the minds and hearts of these characters in the middle of a disaster?

Kate: My story came about because of maternal angst regarding a warming planet and the role of social media in the lives of teens. A lot of the main character’s thoughts and actions probably reflect my own concerns as a mother, caring for my kids, trying to keep them safe, hoping they make good decisions.

In both fiction and real life, I’m interested in hearing about how people prepare in case the grid goes down, water stops running, food becomes scarce. Living on an island and off grid in a rural area of New England, even just for the summer, makes you a little more cautious in your consumption of resources. You store things, grow and then can your own fruit and vegetables, save scraps of thing you might use again. These small gestures helped me to envision, through fiction, what it might be like in an emergency.

Human connection is central in Love is for the Birds. You also write about disconnection and misunderstandings that, when sorted out, help us become better people. Again, there was this sense that the things that make us human, make us who we are, become compromised, and more brittle when our habitat is destroyed. Can you talk about how the weather event impacts human emotions, the decisions we make, the successes and failures?

Diane: In my story, the hurricane not only destroyed a candy store, it destroyed memories. My character inherited the shop from her mother and lost her mother again with the hurricane. Disasters destroy memories. They destroy pictures, grandma’s rocker, recipes and so much more. Jack has lost his wife. He recovers from that loss by helping restore Bird Isle. The Whooping Cranes are always in the background offering hope.

I am interested in your character Billy who is all alone during this disaster. In your book, you depict how different generations react to the disaster. How does climate change impact generations in different ways?

Kate: Aside from being a mom, I am also a teacher to college students. I see resilience in this generation of young people. A lot of interest in what is going on in the news culturally, politically and climate-wise, but also a lot of worry. Billy is a smart kid, but he is also very confused. His mother, Juliet, the protagonist of my story, knows this and is concerned. Being separated in the flood waters doesn’t help. As cliché as this sounds, the helicoptering, what is now also called snowplow parenting (removing all the obstacles that youth need to stumble over to learn and become adults), takes its toll in the crisis I depict. Some kids are completely clueless of basic practical survival skills. Billy talks about this when he joins forces with two teenage girls whose lives have been closely scaffolded by their parents. They have been pressured to be winners in a middle-class world that is quickly disintegrating.

Diane, you have written a love story in the aftermath of a destructive weather event. At times there is a lot of reconnecting with the past and mending of emotions. Can you talk about resiliency? How hard was it to delve into the death of parents and partners, breaking up and getting together? What strategies did you use to tap into these complicated human emotions and dynamics?

Diane: At the risk of being redundant, in my story, the Whooping Cranes represent resiliency. They joined my story organically. But as I researched their history more and more, I realized they were the perfect medallion for my novel. I believe in synchronicity. If an idea keeps poking its head at you, then you need to pay attention. Whooping Cranes exemplify resiliency. They mate for life. That alone is an important value in a romance novel. Whooping Cranes are strong. They fly 2000 miles each year to winter at the Texas Gulf. Whooping Cranes are beautiful. They have a crown of red.

As for death, I don’t think you can write about life without writing about death. Unfortunately, death is as much about life as life is about death. Both my characters struggle with the loss of a loved one. The “death” of the island and the restoration of the island help them realize that death can’t defeat them, not yet. They restore a habitat; they rebuild their store; they find love.

Kate, the Ban of cell phones is a fascinating aspect of Inland. Tell us more about why you included this Ban in the novel. In the book, you said:

“There is such a thing as too much information, vapid and pointless, that muddles what’s really going on outside the window---heat waves, glaciers breaking off, blooming infectious diseases, firestorms in California, the Amazon, Canada, and Australia, a thawing Arctic blanketing our world with expanding rivers.”

How is this “vapid and pointless” information preventing us from addressing climate issues?

Kate: I do think we entertain ourselves into oblivion in a way that has not previously been done. I worry, especially in this political climate, that we are distracted and that certain entities like it that way because it diverts us from keeping track of the inconvenient truths. It’s hard work to think outside the box, push back on convention, question what we are being told. The phones and screens don’t help, especially when we overuse them or children have access to things they shouldn’t. It’s taking a toll on our world: our mental health, our children, the environment.

You end your book on a happy note. Mine ends with some hope. What are your thoughts on hope and optimism in climate fiction?

Diane: Your book inspired me to include more elements of climate fiction in my stories. Fiction builds understanding. Stories encourage people by their emotion, their drama, their truth. Climate fiction can provide a bridge to understanding the realities of climate change without being too dystopian to be off-putting.

As a mother, did writing this book send you on an emotional journey? If so, while writing this book, how did you manage to carry on with your everyday duties with a positive viewpoint? Or, did you?

Kate: Most of this book was written during covid, when everything felt askew and scrambled. I think that facilitated some of the writing, some of the intense emotions that Juliet feels in the book: lots of unknowns, disruptions to routine, family separation, resiliency, deep fear. Writing can be cathartic and this process for me definitely was. I’ve participated in a writing group for many years now and connecting with those people, virtually and in person during this time, was hugely inspirational and calming. We have to keep going in this world, and we have to keep writing.

Find out more about Inland and Love is for the Birds.

Kate Risse was born in Boston and spent summers at her grandparents’ beach house along a central stretch of the Florida Panhandle. She remembers expansive rolling white dunes covered with saw grass and sea oats, wild rosemary, and shorebird nests, much of which have since been paved with asphalt. While weather along this coast has always been unpredictable, the category 5 Hurricane Michael, making landfall in 2018, obliterated neighbors’ houses and animal habitats on the barrier island where Kate spends time with her family, affording a glimpse of what humanity and all living things are up against as the climate changes, and fueling this what if narrative.

Kate earned a Ph.D. in Hispanic Studies from Boston College. She teaches Spanish language and culture at Tufts University, including a course on climate justice. She has published both short fiction and articles on Spanish history. She lives in Brookline, Massachusetts, with her family.

Diane Owens Prettyman is the author of the romantic adventure story "Thin Places" and the twentieth-century historical novel "Redesigning Emma". She is also a frequent contributor to the Austin American-Statesman. Her third book "Love is for the Birds" was released in October of 2024. This novel combines contemporary romance with eco-fiction for an entertaining beach read set on the Texas Gulf.

Diane stays true to her belief that every story has a happy ending, though perhaps sometimes, maybe even often, one has to wait for the perfect finale. Diane lives just a few hours’ drive from the Texas Gulf. She is an avid boogie boarder and spends her summers in the water. Her husband and two black standard poodles provide her room and board in Austin, Texas.

Solutions Spotlight

In The Unmapping, Denise S. Robbin considers the steps needed to make an eco-city:

“When we rebuild,” he reads, “we need to make sure to do it right. Duct tape is step one. Step two, thanks to the city, are the concrete stabilizers. In the meantime, we’re installing solar, microwind, and storage batteries wherever we can to make the grid more resilient. We’re researching ways to remap the city every day. New York is becoming a model for the rest of the world, from Rio to Cairo. From Rio to Cairo? No, sorry, I can’t do this. Can’t you put that in a caption or voiceover or something?”

“Sure, that’s fine.”

New List of Hopeful Environmental Childrens Fiction Released

The Federation of Children’s Book Groups have compiled a list of books about the environment, which includes many books by our members.

Thinking about environmental damage can be a gloomy subject. We wanted to make sure that we were offering a hopeful narrative that stressed positive changes as well as how to mitigate harm.

We wanted to include a variety of genres, including graphic novels and poetry as well as picture books and novels of different lengths, different complexity and that demand different levels of emotional maturity, acknowledging that children have different reading preferences.

It was important to us to find inclusive titles that reflected the diversity of many of our communities because we believe that all children need to see themselves in books. Most of all, we wanted to showcase the very best stories we could find.