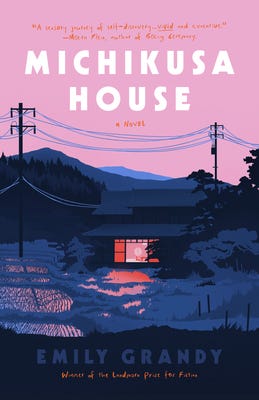

In the first of a two-parter interview, Donna M Cameron interviews Emily Grandy about her novel Michikusa House. Next time, Emily will be asking Donna about her own novel.

After enduring a complicated recovery from eating disorders, Winona Heeley is struggling to return to normal life. Her mother recommends a change in scenery and arranges for Winona to stay with friends in rural Japan, at Michikusa House.

The centuries' old farmhouse hosts residents who want to learn about growing their own food and cooking with the seasons. Jun Nakashima, an aspiring kaiseki chef, is one such resident. Like Winona, Jun is a recovering addict and college dropout. While the two bond over culinary rituals, they change each other's lives by reconstructing long-held beliefs about shame, identity, and renewal.

Donna: My reading of your beautiful debut novel, Michikusa House, is that it is a modern-day meditation on our relationship with food and how our modern way of life, our disconnection with nature, and the consequent degradation of the natural world has adversely affected this relationship. What drove you to write about this subject?

Emily: For me, as a young person, it really was the media presenting images of women we should aspire to resemble and valuing that superficial image over cherishing the body I’ve been given as the miraculous wonder that it is, that was the origin of a complex history of multiple eating disorders. But there were other issues that enabled—or even guaranteed—the development of disordered eating behaviors. I grew up without any culturally based food traditions to teach me what “my people” historically ate, in what combinations and quantities, and in what seasons. The disconnect from where our food comes from and it’s artificial overabundance; the diet culture that makes people think they must starve themselves or follow unnaturally restricted eating patterns; the false notion that outward appearances alone reflect good health…these highly problematic concepts all underpinned my development of multiple eating disorders and, I suspect, many other peoples’ disordered eating habits as well.

With those key issues in mind, I wanted Michikusa House to show what recovery from disordered eating can look like. In addition to learning how to be compassionate with myself, a key element of recovery was learning how to respect the food I eat. I did that by teaching myself how food is grown, appreciating the effort of producing it, and finding beauty in preparing, plating, and consuming meals. A great place to start is by planting a garden. Even just growing one or two herbs or flowers, tending them, and watching them grow can be a revolutionary step toward holistic appreciation of the land that supports us, and the interplay of sunlight, water, soil, and insects that facilitate or hinder plant growth.

Donna: The overgrown graveyard where Winona ends up working is described so vividly. Is this a setting you know intimately? What made you set your novel here?

Emily: Yes! The cemetery is a real place: Lakeview Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio. I encourage everyone to look up pictures. It’s a stunning, historic location with stone mausoleums, giant trees, and picturesque winding paths. It feels especially inviting given that the cemetery grounds abut neighborhoods that otherwise have very little access to green space. The contrast is stark, but it highlights how cemeteries can become such an important refuge for both people and wildlife.

Interestingly, cemeteries once served the purpose that our public parks do now! They were once places people visited to walk and have picnics and enjoy the outdoors. They’ve since lost that appeal for most people, but for that reason they end up being very quiet, peaceful places, which has always appealed to me. And as I discuss in the book, their spiritual significance protects them from development, making many burial places the last refuge for some endangered species. This is a noticeable trend the world over. Burial places are not only significant ecologically, but they represent an idea: that places given special significance are often protected.

Many religious traditions place a strong emphasis on stewardship of the Earth and view the natural world as a sacred gift from a higher power. Back in the 90’s, there was a push to unite religion with the environmentalist movement. This union never materialized on a large scale, but several universities and organizations, including Yale, offer courses and lectures on the topic. These courses celebrate the longstanding contributions of Indigenous people and spiritual belief systems across the globe in offering visions and practices for ecological flourishing. Ongoing studies have even shown that religion—specifically spiritual compassion—can help narrow the political gap between liberals and conservatives over issues of environmental protection.

One of my favourite scenes in the book is the foraging scene…what is the significance of this scene and how does it highlight the theme of the book?

I think the foraging scene is everyone’s favorite! It’s usually the one I read at book talks, and I think there are a few things readers enjoy about it. One is the pacing, getting to walk step by step alongside Winona and Shoko as they gather wild foods along the stream, reveling in that sense of discovery, then that arduous climb up into the mountains, huffing and puffing in the early spring chill to unearth the first green tendrils of spring. What’s not to love about that sense of renewal and optimism in springtime?

Second, I think it’s the lessons Shoko shares with Winona in this scene, about the knowledge held by village elders—of land and how it provides for the people—and how that knowledge is lost when people leave their ancestral lands. I think this lesson speaks to our innermost wild heritage, our deep connection to the places our ancestors inhabited for thousands of years, and how we forsake that knowledge of place when we inhabit urban environments.

That’s not to say don’t respect our urban ecosystems, and I think I make that distinction fairly clear in how Winona begins to relate to the land the cemetery occupies. In fact, I think urban green spaces, even our own backyards, are the perfect places to begin to reconnect with the natural world. But it’s Shoko’s lesson of abandonment of land that sets the stage: why should we bother to reconnect to the natural world in the first place? Because we are part of nature, always have been, always will be. Because nature provides for us, and without many natural systems working in concert we could not have the ingredients to make a delicious soup that warms us on a cold day.

Another favourite part of your book for me was your protagonist Winona’s discovery of the plants in the cemetery – the moss the lichens, etc. Can you talk a little bit about this?

This is a great carryover question from the previous one. Winona’s growing interest about the other beings that inhabit the cemetery is kindled thanks to her time spent at Michikusa House. In her year there, she only left the farm twice (as far as we know), and in that time she and Jun make an interesting observation: their host, Hideyuki Hanada, knows his land better than he knows his wife. Hanada-san has farmed this parcel of land his entire life, he inherited it from generations of family that came before, along with the lessons his ancestors learned about working in that specific plot. The slant of the sun, where the river floods in spring, in what week the seasons change, what types of crops the soil will support…these are all lessons best learned over generations. But we can also kindle that familiarity in the places we inhabit now—for many of us, that’s a city or a suburb. Our backyards and urban parks are not paltry substitutes for wilder places; if you take the time to sit and watch, you can still find hundreds, maybe thousands of species inhabiting these places.

Okay, but why should we care? So what if there’s a racoon living in that tree cavity or a robin nesting up there? Because these creatures are members of the ecosystem that supports us. We need them; they do not need us. All the food we eat relies on a stable environment to grow. We need insects and birds and trees to survive, and they need biologically diverse ecosystems to function. So, if you care about eating and feeding your family, it is essential to care about the non-humans beings we share this planet with.

Plus, they’re just fun to watch! Other species care not at all for the crazy whims of humans. It’s refreshing to watch birds knowing they have no political agenda, they’re not swayed by advertisements. Their cares are fundamental, their songs beautiful…and we are blessed with the ability to sense that beauty and feel gratitude that these beings share their music and their lives alongside us.

On one level, Michikusa House is a coming-of-age tale as your young protagonist negotiates the complexities of romantic entanglements. What were you exploring through the juxtaposition of these two relationships?

I’m so pleased you picked up on this Donna because you’re right, even though Winona is older than your traditional coming-of-age protagonist her growth arc very much shows her coming into her own person and rejecting unhelpful outside influences. In her relationship with Liam, we’re given the sense that she has historically been subordinate, is very reliant on him. When the novel opens, we already see her transitioning away from that, largely thanks to the relationship she had with Jun, in Japan. Jun allowed her to be who she was; I think they were more balanced in that way, more accepting of one another. So, in a way her relationship with Jun served as the steppingstone that gave Winona the confidence to explore who she is and what she wants, rather than rely on the people in her life to establish boundaries and priorities for her.

Your protagonist, Winona Heeley is recovering from an eating disorder. At the end of the book, you list some startling statistics. It made me wonder if these dangerous psychological disorders only occur in the richer countries of our world where there is an excess of food, where life is more complex due to technological advances?

I talked to one reader who worked in remote areas of Africa, and she was very clear: eating disorders are simply not present in those places. When food is scarce, every morsel is precious. When food is abundant and no longer cherished as something hard-won, we take it for granted. Why it becomes a commodity that is abused, like drugs or alcohol, I don’t really know—possibly because it’s something everyone in the developed world has ready access to.

The ending is quite abrupt but (in my opinion) perfect. What made you decide to end your book at that particular point (without giving away spoilers)?

I don’t like picture perfect endings. As a reader, I want a little ambiguity, a sense that maybe the protagonist got what she wanted but in a way she didn’t expect, or that she didn’t get what she wanted, but it ended up being better than expected. Because that’s how life goes! There’s never a clear path, but there are always unexpected twists and encounters. At least, that’s my experience. In Michikusa House, I wanted to show that Winona achieved the independence she craved, but at a cost, while also hinting at possible futures. Will she go back to Japan? Reunite with Jun? I’ve had a couple requests for sequels to fulfil readers’ curiosity but so far have no concrete plans for one.

What are you working on next?

My forthcoming novel, Cupido Cupido, was a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize for socially engaged fiction. I also just finished the first full draft for a YA eco-dystopian, geographically grounded trilogy that I’ve been working on in the background for the better part of a decade, so keep an eye out for those.

Find out more about Michikusa House, and stay tuned next time for Emily’s interview with Donna.

Emily Grandy’s debut novel, Michikusa House (Homebound Publications, 2023), was awarded the Landmark Prize, the Nautilus Book Award, and was longlisted for the Edna Ferber Book Award. Her second novel, Cupido Cupido (forthcoming), was a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize for socially engaged fiction. Her writing has appeared in both scientific and literary journals and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Before she became a biomedical editor for GDIT, she did orthopedic research at the Cleveland Clinic.

Donna M Cameron is a playwright and AWGIE nominated radio dramatist who now writes novels. Her debut, Beneath the Mother Tree was declared a 2018 top Australian fiction read by The Advertiser, longlisted for the Davitt Awards and selected for the 2019 QWC/Screen QLD’s Adaptable program. The manuscript of her second book The Rewilding, which has just been published in ANZ, won her a KSP Fellowship, was runner up in a Writing NSW award and gained her a 2021 Varuna Fellowship. Donna was recently accorded a Regional Arts Development Fund grant to work on her third novel, Bloomfield.

Soil storytelling competition

What if the key to a thriving future is right beneath our feet? That’s the vision behind Tractor Beam’s Climate Fiction Competition, inviting writers and artists to explore soil-centered futures through SOIL PUNK—a genre focusing on regenerative farming, earth-rooted wisdom, and optimism for the planet.

Supported by Tractor Beverage Company, the first USDA Organic Certified brand in food service, Tractor Beam is more than a publication; it’s a future-forward Farmer’s Almanac, inspiring creative solutions for our planet’s future.

The Competition: With $1,500 prizes in three categories (Prose, Narrative Illustration, Judge’s Choice), esteemed judges Joycelyn Longdon (Climate in Colour), Paul Goodenough (Rewriting Extinction), and LinYee Yuan (MOLD Magazine) will select winners who bridge the “Hope Gap” with powerful, soil-based visions.

Deadline: 22nd November

Find out more

2025 NRDC Climate Storytelling Fellowship

The 2025 NRDC Climate Storytelling Fellowship, in partnership with The Black List, CAA Foundation, NBCUniversal, and The Redford Center, is accepting pilot and feature scripts through December 5, 2024!

Fellows will receive $20k, feedback from climate experts, and creative mentorship. To apply for the fellowship, submit a pilot or feature script that engages with climate themes in compelling or unique ways.

In addition to the Fellowship grant, we will also cover one month of hosting and one evaluation fee for submissions on the Black List website. Fellowship recipients will be announced in April 2025. Learn more about how to apply: on.nrdc.org/ClimateStorytelling

The deadline for this program is December 05, 2024.

WHAT MAKES A COMPELLING CLIMATE STORY?...

The script can be in any genre, but climate change and solutions must influence action and/or impact characters.

Climate storytelling highlights the ways that climate change affects characters, influences choices, and/or drives action. A climate story acknowledges that we already live in a climate-altered world and are grappling with the impacts to our homes, health, communities, and jobs. We would love to see stories that highlight communities most impacted by the climate crisis and/or stories that feature characters and communities working toward solutions.

We worry about climate change. We feel shame and grief about it. We talk about it with our partners and friends. People discuss whether it makes sense to have children, or wonder where the safest place is to live, or what they can possibly do to help.

Climate can be a central factor in motivating characters and driving plot. The story and genre options are limitless because climate can touch every aspect of life, from food, health, and relationships to justice, jobs, and national security.

Many climate stories in mainstream entertainment depict extreme weather disasters, societal breakdown, and apocalypse. That dark and narrow vision is understandable, and it can be entertaining, but if all the climate stories we see show characters stuck in despair, or in dystopian futures, it reinforces the view that there’s no way out. It also overlooks the enormous potential for original content that illuminates the more complex and nuanced human reality of the climate crisis, including stories about people fighting for a healthier, more equitable and sustainable future.

We need it all–the bleak and the inspirational, the fantasies, dramas, comedies, and rom-coms. It is the power and privilege of writers to show us how climate change is transforming our world, and to help us find a path to salvation. This program aims to support well told stories with climate themes that entertain viewers and allow them to engage with the range of emotions caused by the climate crisis. Our general frame is that if a story works artistically, it’s a great way to approach climate and we hope that submitted scripts continue to reflect a diversity of characters, settings, and tones.

We encourage you to clearly highlight your script’s climate connection in your submission materials, as only qualifying scripts will receive a script waiver.

WRITER'S RESOURCES:

Rewrite the Future: Learn more about Rewrite the Future, NRDC’s initiative to help Hollywood take on the climate crisis. Watch their Sundance panels (presented by NRDC and the Black List) for tips and resources to guide your writing.

The Last Laugh: Comedy in the Age of Climate Change (Sundance 2024) featured Quinta Brunson (“Abbott Elementary”) in conversation with Mike Schur (“The Good Place,” “Parks and Recreation,” “Brooklyn 99”) about tackling tough topics through comedy, why laughter is the best medicine, and how climate change can unlock creative opportunities.

The Big Picture: Representing Our Climate-Altered World On-Screen (Sundance 2023) brought together a panel of Hollywood professionals to discuss creative strategies for representing climate in film and on TV.

More Than a Feeling: Climate Emotions in Film & TV (Sundance 2022) brought together mental health experts and Hollywood storytellers to discuss how to represent climate emotions in entertainment to better reflect our lived responses to the crisis.

Beyond Apocalypse: Alternative Climate Futures in Film and TV (Sundance 2021) gathered filmmakers and climate leaders to discuss how entertainment stories can help us see, feel, and build the climate future we want.

Sustainability Onscreen Tipsheet:

This tipsheet offers a wide array of options for creators and producers interested in representing climate and sustainability onscreen.

Green Production Guide Creative Resources: The PGA and Sustainable Production Alliance have a variety of creative tools available on the Green Production Guide site.

ALBERT Editorial Toolkit: The team at BAFTA’s albert program has put together a comprehensive creative guide on how to incorporate climate and environmental stories into content.