Writing a love story to Antarctica

by Midge Raymond, plus an interview with Aya de León about her new novel A Spy in the Struggle

There are details of a book giveaway at the end of the newsletter - fill out the form to enter!

For me as a writer, place is essential to character. Every setting, whether an American city or an icy continent, has a personality, and where a character lives, or is from, is so vital to me in understanding that character. So I always begin a story not only with a character but with a sense of place.

In writing My Last Continent, Antarctica itself became a character of sorts—in the novel, the continent becomes part of a love triangle between Deb and Keller, who are both so strongly connected to Antarctica in their own ways, for their own reasons. For Deb, Antarctica is part of who she is, and there is no place else she can imagine being.

Visiting and researching Antarctica taught me so much about those who spend their time at the bottom of the earth—and most intriguing to me, I think, are the non-humans who live in Antarctica: whales, seals, seabirds, and particularly penguins. It’s hard not to love such adorable creatures, but what I love most about penguins is that they are among the most persistent animals in the world, striving every season to raise a new generation as they face a world that is less and less hospitable to them.

Antarctica is experiencing climate change more rapidly than nearly any other place on earth, and yet there is still great hope for the continent and its creatures—as long as we all realize that despite its location at the end of the earth, we are all very closely connected to this faraway place, and we need to do all we can to protect it.

“Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Elizabeth Bishop asks in her poem “Questions of Travel”—the same question I am asked often when I talk to readers about My Last Continent. Would it be better for Antarctica if we all stayed at home?

Antarctica is not a country and has no permanent human residents. Yet in the twenty-first century, it is becoming a hot spot for travel.

The first 57 citizen-explorers visited Antarctica in 1966, and by the time I visited in 2004, the continent was seeing about 20,000 visitors a year. According to the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO), by 2012, Antarctic tourism increased to nearly 27,000, and it was around 40,000 in 2019—down from the busiest season the continent has ever seen, which was 46,265 in 2007-2008). Now, the global pandemic has given the continent a break—but when travel resumes around the world, should we be going to Antarctica at all?

While My Last Continent is about a catastrophic shipwreck, travel to the Antarctic is historically quite safe; however, this does not mean it is without danger. Despite such technological advances that make polar travel easier and more comfortable, a ship is only as safe as her captain—and due to the capricious nature of ice and polar weather, even an experienced captain isn’t immune from human error or the whims of the wild seas that surround Antarctica.

And, as the story of My Last Continent makes clear, when it comes to polar cruises, bigger is most certainly not better. This article in The Guardian (titled “A new Titanic?”) made the point very clearly: “If something were to go wrong it would be very, very bad.”

Another issue with big ships is their environmental impact. All travelers should carefully vet their tour operators, making sure they follow the guidelines of IAATO, and choose a company with vast experience in ice-filled waters. The Southern Ocean is highly unpredictable, and an experienced captain, crew, and staff makes all the difference—not only for the safety of passengers but for wildlife as well. Check out Friends of the Earth’s Cruise Ship Report Card before booking a trip (in its 2020 report, no major cruise line earned a grade higher than a B-minus; most grades were Ds and Fs).

Better yet, enjoy the last continent from afar. Web-based citizen science programs like Zooniverse offer virtual experiences—for example, a chance to count penguins and identify individual humpback whales in Antarctica. From our computers, we can “travel” the world, see incredible sights and creatures, and contribute to ongoing research efforts.

Sometimes it takes visiting a place to fall in love with it and become inspired to help save it—and this may well justify our carbon footprints in the end. Which brings me back to the question: Should we stay home? There is no easy answer. But those of us who have the luxury of asking the question might consider that, for the sake of the planet, the oceans, and for future generations, the road less traveled—or not traveled at all—does make all the difference.

Antarctica is sometimes misunderstood as a plain, vast, white place—which, of course, it is—but it’s also a continent brimming with amazing colors (among them: the reds, oranges, and violets of its sunsets; the bright greens of the aurora australis; the reds and greens and browns of its algae; and the myriad shades of blue and white that comprise icebergs).

Also among the most amazing—and the most overlooked—aspects of Antarctica are its sounds. For example, listen to the sounds of icebergs rubbing together here. It sounds a bit like furniture breaking apart, and then a little like a penguin colony from far away, and finally it becomes something completely otherworldly.

And scientists have recorded the wonderfully eerie sound of wind whipping across the Ross Ice Shelf, which creates an unearthly humming noise. These recordings were gathered by scientists who spent two years recording the “singing” of the ice via 34 seismic sensors. They realized the winds caused the vibrations on the ice, creating a constant hum that will help researchers study changes in the ice shelf, such as melting, cracking, and breaking.

What I found most remarkable about Antarctica is the silence—that is, the sounds of spaces with no human presence at all. It’s impossible to capture in a video or audio, but I did try to capture the feeling in My Last Continent: “…we listen to the whistling of the wind across the ice and the cries of the birds. I savor the utter silence under those sounds; there is nothing else to hear—none of the usual white noise of life on other continents, no human sounds at all…”

There are very (very) few places on the planet that are as free of human sounds. Nearly every single sound is natural, whether it’s the wind, the rush of the sea, the calving of icebergs, or the sounds of penguins.

Much like the character of Deb in My Last Continent, I’m concerned with how the penguins are faring in a world of chaos (including climate change and, until the pandemic, increasing tourism). So, how exactly are the penguins doing?

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, of the eighteen species of penguins listed, four are stable (the Royal, Snares, Gentoo, and Little penguins), two are increasing in numbers (the Adélies—in 2018, a “supercolony” of 1.5 million Adélie penguins was discovered in the Danger Islands—and the Kings, who are widespread, from the Indian Ocean to the South Atlantic, and yet, according to one study, are being forced to travel farther for food, which means that their chicks will be left on shore to starve). The status of the Emperors is classified as unknown, and when it comes to the remaining penguin species of the world, their numbers are all decreasing—and in some cases, they are decreasingly alarmingly fast.

The penguins in the most danger of becoming extinct are the Galápagos penguin (with an estimated 1,200 individuals left), the Yellow-eyed penguin (with fewer than 3,500 left), and New Zealand’s Fiordland-crested penguin, also known by its Māori name, Tawaki, meaning crested, which the IUCN lists at between 2,500 and 9,999 individuals (yet local researchers’ estimates are of only 3,000 individuals).

These are pretty scary numbers—and the itinerant lives of each of these endangered species make them very hard to accurately count, which means that while there could be more than we think, it’s likely that there could be far fewer than we realize.

So, what can we humans do for penguins to help make the world a better place for them? Here are a few ideas to start.

Re-think our consumption of seafood—especially krill (and health supplements containing krill) and farmed fish, who are fed krill. Overfishing is one of the biggest causes of penguin death, whether it’s because humans are eating their food (krill numbers have declined 80 percent in the last 50 years) or because they are killed by fishing nets and longlines. Even “sustainable” seafood has an impact on the oceans and wildlife.

Be a thoughtful traveler and a respectful birdwatcher. If you must travel to see penguins (and it’s pretty irresistible), choose places that can handle your human footprints—and always go with eco-friendly tour companies. Once there, always pay close attention to guides and naturalists who know how to keep a safe distance. If you’re traveling without a group or guide, be sure to study up; learn about the birds’ habitat so you can be sure to stay out of their way.

Do all that you can to combat climate change. (See the Climate Reality Project and Cowspiracy for some good tips.) Over the last six decades, scientists have observed an average increase of 2 degrees Fahrenheit per decade on the Antarctic peninsula. For the penguins especially, climate change isn’t an abstract, faraway notion: It’s happening before our eyes, chick by chick.

Learn more by visiting such organizations as Oceanites, and support such organizations as the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, which protects all oceans and creatures, and such conservation efforts as the Center for Ecosystem Sentinels, which monitors penguins and works on the ground to ensure protections for them.

Become a citizen scientist. Penguin Watch is a completely addictive website that uses citizen science to help study penguins. Be warned — you may lose hours to penguin counting! But at least you’re doing it for science.

You can find out more about My Last Continent here.

MIDGE RAYMOND’s writing has appeared in TriQuarterly, American Literary Review, Bellevue Literary Review, the Los Angeles Times magazine, the Chicago Tribune, Poets & Writers, and many other publications. Midge worked in publishing in New York before moving to Boston, where she taught communication writing at Boston University for six years. She has taught creative writing at Boston’s Grub Street Writers, Seattle’s Richard Hugo House, and San Diego Writers, Ink. She has also published two books for writers, Everyday Writing and Everyday Book Marketing.

New Release

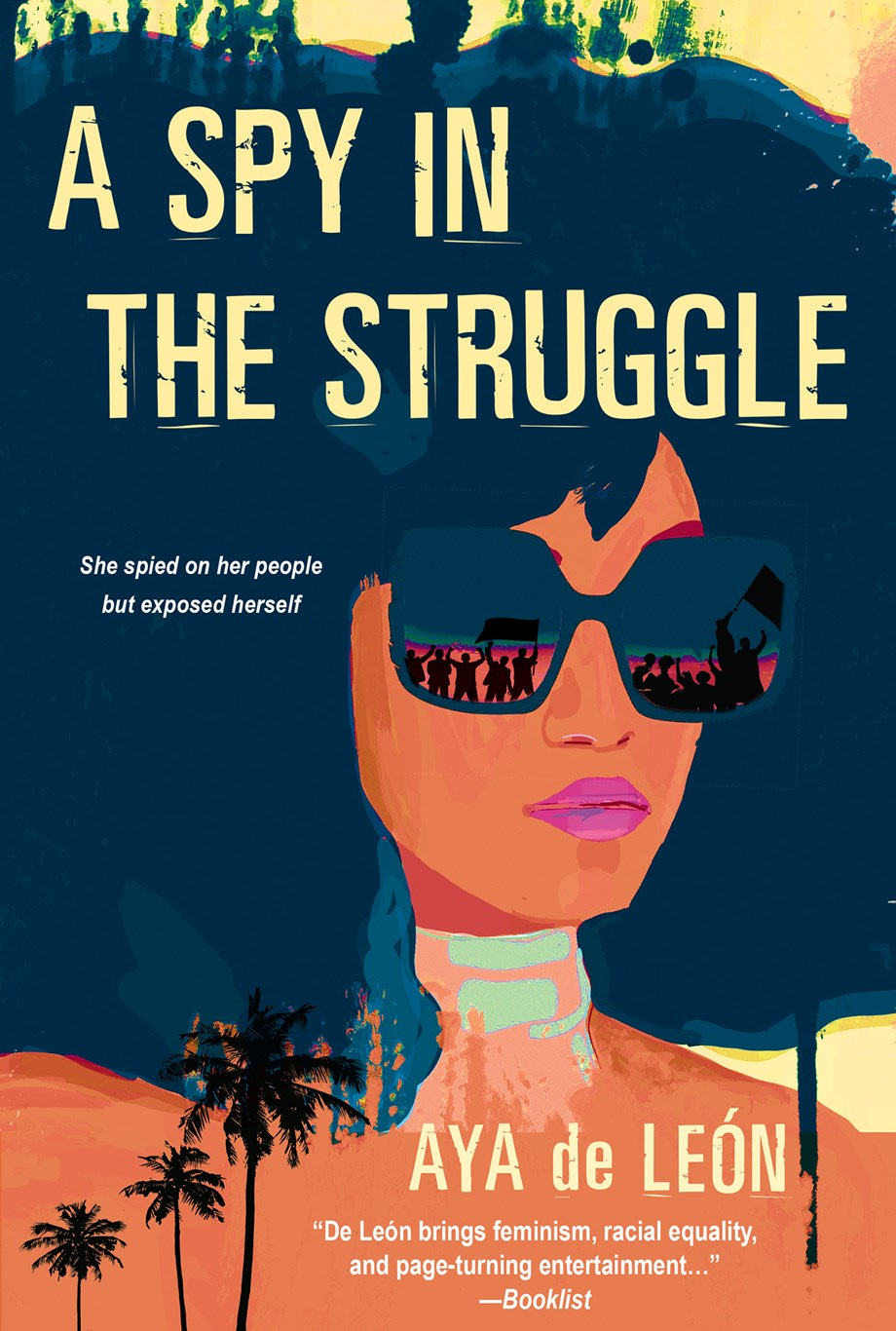

A Spy in the Struggle by Aya de León was published this month by Kensington Books. I talk to the author of the adult thriller about her new release, and her motivations for writing about climate change.

Tell us about your new book.

A Spy in the Struggle is about a millennial Black woman who has followed all the rules, but can’t seem to find the success she’s been promised. She graduated Harvard Law and joined a top corporate law firm, but when they’re indicted for securities fraud, she turns whistleblower to cover herself. Then, when she can’t get another job in corporate law, she goes to work for the FBI. They send her to infiltrate a Bay Area eco-racial justice organization. In the process, she begins to have doubts that she’s on the wrong side.

How does climate change play into the plot?

This multi-generational organization has an ongoing campaign against a biotech company in their low-income Black and Brown Bay Area city. It’s sort of every horrible environmental scourge possible, from toxic dumping to rising cancer rates near the lab to producing dangerous chemical weapons. They are also the prototype shady corporation promising capitalist solutions to climate change, in the form of designer biofuels that they promise will have zero emissions, but actually have a huge carbon footprint to produce. Also, there’s a critique of a fictional mainstream environmental organization that has created a number of nature preserves and solicited donations based on those holdings, but it comes out that they are also allowing fossil fuel drilling on those lands. It is actually in response to this scandal that the mainstream green organization begins funding these multi-cultural projects throughout the US. However, because they are so poorly funded, they are generally ineffective. However, this particular one is very effective, and attracts the attention of the FBI.

The organization is focused on youth leadership and is making clear connections between racial justice and climate justice.

What kind of research did you do when writing it?

I started writing it in my 20s, when I was part of an intergenerational African American community organizing group. We speculated about what would happen if we were ever infiltrated by the FBI. In the early 00s, I decided to include an environmental justice angle. Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything was important in grounding the deceitful practices of mainstream environmental organizations. I also had to study FBI procedures to get those details right.

What are some of your favourite books about climate change?

On Fire: The (Burning) Case for the Green New Deal by Naomi Klein.

Can you remember when your journey with climate activism started?

I had been “concerned” about climate change, but everything came home to me with Hurricane Maria in 2017. I am part of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, and I could no longer look away from the issue. I began to call myself a climate activist. I wrote SIDE CHICK NATION, the first novel published about Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico in 2019. Later that year, I became active in climate organizing. In 2020, I became a founding blogger with The Daily Dose: Feminist Voices for the Green New Deal.

Why is it so important for you personally to see climate change discussed in fiction?

Currently, people are obsessed with books set in the past or in the dystopic future. It’s as if we want to rewind to the time before the crisis was looming, or fast forward to a time after it’s all fallen apart. We don’t want to be in the time when we need to take action. Which is why I think it’s necessary to set books in the present where protagonists are compelled to begin to act on the climate crisis. This is true of Side Chick Nation, as well as another of my novels-in-progress.

What message do you hope readers will take away from your work? What steps would you like them to take to be more involved in climate activism?

Whoever we are, wherever we’re from, wherever we live now, and whatever we’re doing, climate is our issue, and the climate movement needs us. The biggest shift right now needs to be from the encouragement to do individual things, particularly with regard to consumer waste (reduce/reuse/recycle) to putting our energy toward policy changes at the corporate, military and governmental level: (Green New Deal/cutting the military budget/ending fossil fuel dependence). It’s no longer about individual solutions, but planetary ones.

You can find out more about A Spy in the Struggle here.

AYA DE LEÓN directs the Poetry for the People program in the African American Studies Department at UC Berkeley, teaching poetry and spoken word. In spring 2021, she will be a visiting professor in the graduate creative writing program at the University of San Francisco. Aya is a founding blogger with The Daily Dose: Feminist Voices for the Green New Deal, and she organizes with the climate movement and the Movement for Black Lives. Aya has organized elementary school students for the climate movement, and has written about it for Mutha Magazine. She also delivered the 2019 Afro ComicCon keynote address on Afro-Futurism as a call for Black people to join the climate movement and save the future.

Giveaway

To enter to win a bundle of advanced copies of upcoming Middle Grade climate fiction, including Melt by Ele Fountain, The Last Bear by Hannah Gold and Burning Sunlight by Anthea Simmons, fill out this form.

Climate Change in the News

The Paris climate pact is 5 years old. 5 youth activists share their hopes for what’s next. [Vox]

The Biggest Climate Wins of 2020 [Gizmodo]

How to Defeat the Fossil Fuel Industry [The Nation]

Paris climate agreement: 54 cities on track to meet targets [The Guardian]

UNEARTHED - essay by League member James Bradley [Meanjin]

League member Kate Kelly's top eco-adventure story writing tips [The Guardian]

How Fiction Can Persuade Readers that Climate Change is Real [Euro News]