A brief thread on ‘sanctimony literature’

Or, the risks and rewards of writing eco-fiction while working on environmental issues

by A.E. Copenhaver

In an essay published in Liberties journal, critic and philosopher Becca Rothfeld brilliantly topples a few monoliths of contemporary writing by declaring them ‘sanctimony literature.’ After first commenting on some of the “riskless and conciliatory” novels (and novelists!) of the 21st century in an essay for The Point, Rothfeld then more deeply mines this trend of simplistic and performative wokeness in modern literature. She notes that often these novels are full of characters who are “stupefyingly smug,” who never display any “genuine curiosity about what it really means to be good, [... and who are] blind to the distinction between morality and moralism.”

This fantastically satisfying examination of performative wokeness in literature is just too good—and reading Rothfeld’s essay in full is totally worth the $50 annual subscription to Liberties journal.

And I say this as someone who not only has written a novel that could, at certain angles, slot into the sanctimony literature bookshelf (according to some readers, anyway), but also as someone who has spent most of her professional career—at various times and with varying intensities—standing very closely to and even bumping elbows with some of the more performative versions of “the many aspects of goodness” explored in Rothfeld’s essay.

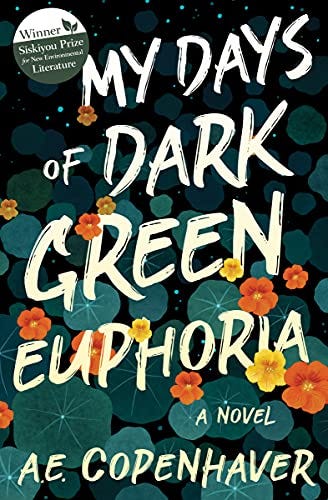

So, it’s no coincidence, then, that upon recognizing the fruitful landscape of working in the environmental sector, I heard, with ever increasing insistence, the loud and excoriating voice of Cara Foster, the protagonist of my first novel, My Days of Dark Green Euphoria.

Cara Foster can speak for herself, so I won’t attempt to explain her perspective here. But crack open my book without noticing the ‘vegan literature—satire’ designation in the front matter and you, too, can be offended and outraged by Cara’s unrelenting judgments of everyone who eats animals, drives to Target for casual shopping sprees, who likes donuts, smokes cigarettes, takes long, hot showers, who flies in airplanes, who maybe doesn’t recycle, and who enjoys having pedicures.

My dear aunties once told me—to my great delight—something to the effect of: You might make some people very upset with how ruthless Cara is.

To me, the possibility of this upset over Cara’s perspective serves as evidence of two possibilities: one, that I failed as a writer to make Cara a satirical character, and two, that readers are really and truly listening to what Cara has to say—and they might not like it one bit.

And this could be precisely what is so intriguing about Rothfeld’s criticism: just as characters from so-called sanctimony literature seem eager to demonstrate their own politics and then condemn everyone else for theirs, modern day readers, too, appear primed and even enthusiastic to judge, condemn, call out, and to feel offended and outraged by these same characters.

It is in this sense that the ethics of reading come into play. At what point and with what consequences do readers feel justified in slamming a book shut and refusing to read further? Perhaps when the protagonist is a pedophile or murderer (or both)? Perhaps if she’s a vegan with climate anxiety suffering from compassion fatigue and zero anger management? Or maybe it’s more to do with the author’s failure to execute the character to achieve the desired reading experience. Either way, both insufficient portions and heaping measures of ethics in fictional protagonists can be wonderfully and richly engaging if well executed.

And in the professional realm of environmental protection or social justice advocacy or climate action, or defense of human, land, and animal rights, we workers offer ourselves up daily to criticism from our own kind. Are we aware of our privilege enough, and do we acknowledge it too much or too little? Are we unknowingly or purposefully perpetuating systems of oppressions in the way we speak or write or host meetings? Are we exemplifying the savior complex? Are we making everything worse simply by showing up or attempting to contribute to this work at all?

Clearly, I don’t have the answers. And while I intend to keep up my work both on and off the page, I believe reading and conversing with literature—in its myriad forms, whether sanctimonious or not—is one of the best ways to wrestle with these very difficult and important questions.

Because for as sanctimonious as so many contemporary narrators and characters are accused of being, readers (and critics) sure do seem to enjoy engaging with them—especially if those same readers either cannot tolerate the politics, ethics, tone, or messaging contained therein enough to read the entire novel, or if instead those critics choose to write thousands of words about how problematic and derivative and simplistic and self-righteous all this sanctimony is.

Alternatively, we might consider: What is the greater significance of so-called sanctimonious narrators in modern literature? What is their relationship to the climate crisis or the sixth mass extinction we are all experiencing? What are they really saying and how are they saying it? The more readers and critics (such as Rothfeld) contemplate these and similar questions, the better our collective understanding and imagining of the human and beyond-human experience in the 21st century will be. Otherwise, our own imaginations could turn out to be the last safe space.

A.E. Copenhaver is a writer, editor, science communicator, and climate interpreter. In her current position with the International Arctic Research Center, she helps run the Study of Environmental Arctic Change, a research collaboration funded by the National Science Foundation. Her debut novel My Days of Dark Green Euphoria won the Siskiyou Prize for New Environmental Literature and was published by Ashland Creek Press in early 2022.

Writing Climate: Pitchfest for Film and TV

DO YOU HAVE AN IDEA FOR A CLIMATE-RELATED TV SHOW OR FILM?

All hands on deck! If you’re a screenwriter who's concerned about the climate crisis, we want to hear your climate-related story pitches for TV and film. 24 winners will pitch in person or virtually – one on one – to Hollywood executives at the 2023 Hollywood Climate Summit.

WHAT IS THE CLIMATE PITCHFEST?

Many Hollywood projects are tackling climate change and the multitude of ways it affects life on earth, but we still need more voices that envision new possibilities for the world and create lasting cultural impact. Writing Climate: Pitchfest for TV and Film celebrates the best unproduced climate-themed scripts in film and television by connecting the writers of those scripts to Hollywood executives, producers, agents, and/or managers through curated one-on-one meetings.

NB: Lauren James, founder of the League, entered this pitchfest last year and got to the finals. She was given training on preparing a video pitch (which you can watch here) and pitched her story to multiple executives. It was a fascinating learning opportunity, with the chance to meet lots of like-minded climate writers!

Solutions Spotlight

In this extract from a book featuring a climate solution, Donna Glee Williams shares an extract from The Night Field about the re-wilding of agriculture:

As we got close to my field – our field, now – I heard a frail high cheeping in the night. Peepers. Tears sprang to my eyes. Could it be? Frogs already? It had been so long since I’d heard their voices. Was that all it took to bring them back – just a few months without the poison? Could things truly heal so fast? My heart sang and I cheeped back to them, one more voice in the night.

Lakka looked at me. ‘Now? Out here? You’ve picked this night to finally go crazy?’ She was trudging heavily, weighed down by the full sprayer on her back. It was a long way to the fields by the river.

I cheeped again. ‘Don’t you hear them, Lakka? The frogs? They eat bugs – any bugs. All bugs. Cutter-bugs, Lakka, cutter—’

And that’s when the hound hit her.

Learn more about natural pesticides from the charity Pesticide Action Network.

Having taught satiric literature over several decades and My Days of Dark Green Euphoria this past fall, I heartily commend A..E. Copenhaver. Her novel achieves the daring and difficult feat of satirizing her extreme environmentalist protagonist without dismissing her concerns and ecogrief as merely extreme or unwarranted. I look forward to teaching it again next year, along with this cogent essay.

--John Sitter, Prof. Emeritus, Emory University